2024-06-14

Does your employer care about your wish to work multilingually? And does it matter what your co-workers think about your multilingual aspirations? A recently published sociolinguistic study explored the wish (and empty promise) of élite multilingualism in the context of EU workforce mobility.

Image credit: by Drazen Zigic on Freepik

Research summary written by Veronika Lovrits, BM Luxembourg

In today’s international labour market, language is a powerful tool that influences professional success. Many people choose to work in international settings to enhance their multilingual skills. However, the opportunity to do so doesn’t come automatically, as language use can be manipulated by language ideologies.

Language ideologies provide a simple mental shortcut for deciding which language is “better” and how to “value” the person who uses language in a certain way. The problem is that the beliefs these ideologies support are not checked against experienced reality. This can lead to impractical and unhealthy work conditions, creating tensions in the international workplace.

A recently published study from a terminology and communication unit in an EU institution revealed that the joy of multilingualism can turn into a silent but fierce discursive battle. The study was based on iterative interviews with the unit’s permanent staff and trainees on a paid five-month traineeship (five cohorts in total). The participants reflected on their language use, its reasons, and its effects from 2017 until 2021. Their stances were qualitatively analysed in 2023 and 2024.

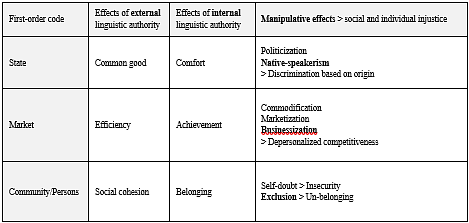

Table: Theorised aspects of linguistic authority

The table can be retrieved in full size after downloading the report at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01434632.2024.2321394

Results exposed a difference in the perspective of the “rooted” and “routed” employees—those with stable positions versus those facing job uncertainty and the looming push for further transnational mobility. The former could enjoy the positive effects of language use, whether through the use of English as the common vehicular language or the pragmatic choice of multilingual exchanges. In contrast, the “routed” employees, whose end of contract with the EU institution would mean leaving Luxembourg, had to bear most of the negative effects of language ideological manipulation.

While the official European Union discourse promotes multilingualism as a means to ensure democracy and linguistic justice, this turned out to be rather an empty promise for the internationally mobile trainees. Indeed, the discourse celebrating multilingualism did not have the same effects on permanent staff as it does on the youth eager to prove themselves as linguistically competent professionals in the international labour market. The perceived uneven discursive positioning due to the prevailing English native-speakerism led some of the team members to mutual micro-aggressions, as the “non-native English speakers” were trying (in vain) to discursively resist unjust linguistic privileges and gain more recognition in the team - a pattern observed over the years in the changing team constellations.

But it's not all doom and gloom. The study also exemplified how organizations can empower their teams to challenge language ideologies by fostering critical metalinguistic awareness and reflection on linguistic authority (i.e., who or what defines which language is best to use). However, achieving the positive effects of linguistic diversity will require education towards critical language awareness and more lucid managers who care for the workers' well-being.

Are you interested in more details?

The full academic report is available here

You can also check earlier reports from this research, which discussed the topics of:

* * *

Further reading